Galina Moskaleva, Vladimir Shachlevich ‘Durdom’ series \ 1989

Galina Moskaleva ‘Childhood Memories’ series \ 1989-1990

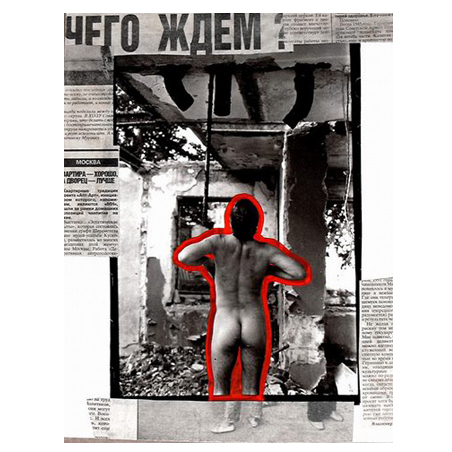

Vladimir Shachlevich, ‘1991. Belarus’ series \ 1991

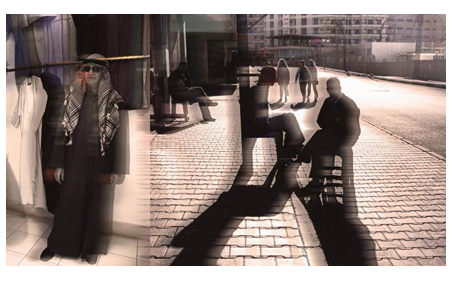

Vladimir Shachlevich, ‘Ordnung’ series \ 2007

Galina Moskaleva, ‘Museum’s supervisors K-21’ series \ 2005

Galina Moskaleva, Vladimir Shachlevich ‘A Fitting room’ series \ 2007

Galina Moskaleva, Vladimir Shachlevich ‘A Fitting room’ series \ 2007

Galina Moskaleva ‘Death: is it A Big Picture?’ series \ 2012

pARTisan #20’2013

Photo artists Galina Moskaleva and Vladimir Shachlevich are at the origins of the modern Belarusian photography. In the mid-1980s, they got to the studio of Valera Lobko, though each in their own way. Later on, the phenomenon of this studio was marked as Minsk School of Photography. Their lives have come different ways. Galina and Vladimir live and work in Moscow, but occasionally they visit Minsk and remind their colleagues of those recent and at the same time already distant times.

— What was Minsk cultural underground life like in 1980s?

Galina Moskaleva: In those days we were as if hiding in the dungeons, were constantly under the pressure of some inspections, so we could not freely exhibit our works. But perestroika was coming, and we got the opportunity to arrange exhibitions in the Red Church, for example, where the Cinema House was located at that time. However, most of these exhibition shows didn’t last long: perestroika came, but not yet in the minds of people.

For example, I had a picture of a grand piano with the words “Belarus” engraved on it. Under the piano, there was a basket with apples and a pig’s head and some other things in it. The picture actually had a kind of twisted conceptual plot. So, I was asked, “Do you mean to say that the Belarusians are pigs?” I was stunned, and replied “Why do you think so?” “Because here you have a grand piano “Belarus”, and a pig’s head under it. Is this what you are implying?”

That was the essence of the Soviet system: there were some special services agents who might not think that way themselves, but were searching out the “wrong” thoughts.

Vladimir Shachlevich: Those years were really a turning point for the history of art. We had an ironic look at the development of a modern consumer society, and had a radical interpretation of the world which was indifferent to art. Despite the fact that we lived in a complete cultural isolation, we somehow managed to feel that irony and radicalism.

Given the context and the specific conditions of existence, we managed to feel that time and find an embodiment to it. This was done either through our own “I”, our relatives, and informal surrounding. This called for new tools and means of expression.

In my studio, I imagined myself a surgeon who performed operation on sick society. I did photo montages, namely, I cut, fixed with a cellotape and made a few layers. While printing, I was experimenting with film, lighting, color and film development. I liked various scratches, torn edges, perforation holes, and a full frame, in other words, I liked everything that was considered to be deficient in traditional photography.

— How the situation changed for you after the collapse of the Soviet Union?

G. M.: It was a favorable time for us because Western critics, curators, museums and galleries were showing a huge concern to Soviet photography. We were a closed country, so it seemed to them that there were bears running around and they had to bring their own spoons when visiting our country. In 1993, the Union of Photographers of Russia organized a large photo preview in Moscow. At these previews we showed ourselves to be the Belarusian School of Photography. Both Western experts and we ourselves saw that our works differed greatly from the works of Russian and Ukrainian colleagues.

— Do you think there is the Belarusian School of Photography?

G. M.: Surely, and it’s not only my understanding. This is also stated in the discourse of Western and Russian critics. First, they were talking about the Belarusian school, then became more specified and started to talk about Minsk school. In 1990, in Moscow Cinema House we made an exhibition “Belarusian avant-garde”, and in 1994 in Berlin “Ifa-Gallery” an exhibition “Fotografie aus Minsk”. There was formed and the main circle of Minsk photographers, namely, Vladimir Shachlevich, Sergey Kozhemyakin, Igor Savchenko, Uladzimir Parfianok and me. We did not decide it ourselves.

Simply it happened so that during every preview our works were chosen. Together, we exhibited our works in Germany, Sweden, the USA, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Poland, and Russia, St Petersburg and Moscow. When our works were purchased for the collections of Western museums, we were always wondering why it was exactly we. I was later explained that we had been able to create such photographs that fully reflected their time, and that we had used the language of modern art to do this.

— You said that Minsk School of Photography differs from Moscow and Ukrainian. What is the difference then?

G. M.: We had one country – the Soviet Union, and each of us was in our own dungeons, in Moscow, Kharkov or Minsk. We communicated, though. For example, Boris Mikhailov often came to Minsk from Kharkov, and we worked with similar themes and ideas. But if, for example, one looks at the book “PHOTO / Manifesto” written in 1990 by the Americans Walker, Ursitti and McGinniss, they can see an obvious difference.

Minsk photos are more metaphysical and conceptual, while at the same time, initial materials are actively transformed by means of chemical coloring, working with several negatives, and theatricality. In this way, we were reflecting the reality.

Moscow photography was mostly black and white; it illustrated symbols of time in a simpler and more direct way. Kharkov photography was the most cynical and made in the style of anti – aesthetics. Aniline dyes were very popular then, which made images even more cynical.

— Your works are characterized by a certain kind of aesthetics. Yet they clearly deal with social issues, which is quite far away from traditional photography not only in terms of form, but also in terms of the atmosphere. Did this style appear in Łabko’s studio?

G. M.: Yes, before I met Lobko I was taking usual photos, such as portraits, reports, and still-lives. If, for example, I was taking the psychological portraits, I was not thinking about the essence of the person. For me it was enough to find the right angle. Lobko directed my look in the depth of a human being. He did not teach me a philosophical theory, but he made me a deeper person due to influence of his personality. He made me ask myself an endless number of questions. Thus, it triggered me in a special way, though with other people it could have been different.

Some people, for example, looked at everything that was going around through cynicism. I also came through a time when I wanted to throw out everything I did not like about the Soviet system. For example, once I was given a task to take photos of elections. At 4 in the morning I was taken to a polling station with a ballot box to meet the first voters. But they came only to buy oranges and tangerines because it was the only place where they could buy them. Surely, I did not like it. Therefore, I took the pictures and later painted them an eerie blue.

By doing so, I released all negative emotions that I had, though, not in relation to men, but to the system that I did not accept on a subconscious level.

Then I started thinking who I was. Who was I to judge and act that way? I turned to my dad’s first films with pictures of me as a child. I was trying to understand judging by these photos why I had come to this life, what I had to do and why I was acting in this or that way.

Thus, there appeared a series of pictures “Childhood Memories”. I needed knowledge given to me by Valera Lobko. My father took the pictures of me, but how could I transfer the moment that was caught 25 years ago? I was looking at the photos and felt that I needed dynamics, because all of them were static, although memories could not be static in any way. I began to develop the films. It was necessary to emphasize color, so I needed bends. This work is very fast, chemicals can rapidly change images like watercolors do. Thus, I had to stop the process just at the right moment. I worked for about 10 years, and finally received a series which is now in museums and collections.

V. Sh.: I can also give a small example from my experience. In 1980, I was doing a series of shots of best workers from the kolkhoz “The Red Flag” to be placed on the board of honor. It was a very well-paid job. It was necessary to make a zooming in, so I took a large-format camera “Moskva” which only allowed to take photos of the best workers in full growth. We were taking photos in the field. We used a bed throw as a background. Some of the guys were holding it like a banner. When printing the photos, I framed the images and received the standard portraits of the best workers , as required.

In 1989, Galina and I were invited to take part in the project “LITSA: a modern portrait in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus” organized by the Dutch curators. I printed the original negatives of the best workers. They showed the whole process of shooting: the bed throw, the hands of my colleagues who were holding it, the edge of the house, and the field. The whole process of creating a portrait for a board of honor was shown. This series has been exhibited at several biennials, and this year I have been invited to “FotoFest” in Houston.

— Are there any “taboo” topics for you as authors? Do you set limits for acceptable and not acceptable in your work?

G. M.: I don’t take photographs of such things which I don’t personally accept. For example, I do not like porn, so I will not photograph it. I do not want to do untrue things or any cynical stuff. Although sometimes we need to have some reasonable cynicism. But I’ve been trying to avoid the negativity, as we’ve had enough of it. Now I just want to live. But this does not mean that I will not work with difficult topics. For example, my latest project about death is called “Death: Is this the Big Picture?” I see a big picture of life in this topic.

All of a sudden, it emerges fully and truthfully. One becomes aware of death, which gives an understanding that people’s lives do not end after a physical death.

Translated by Sviatłana Sous (briefly)

Photo © Galina Moskaleva, Vladimir Shachlevich

Opinions of authors do not always reflect the views of pARTisan. If you note any errors, please contact us right away.